Seventeenth century cafes

The earliest story of selling coffee in Paris dates from 1671, when an enterprising Armenian named Pasqua Rosee set up a stall in the Saint Germain area – complete with a tent filled with flamboyant furnishings, typical of a Turkish coffee house. He roasted and brewed the coffee himself and employed Turkish boys to serve it. They wandered around the streets with trays from which they sold a ‘petit noir’ (small black coffee) to any curious member of the crowd.

After the fair, he opened a café at Quai de l’Ecole near the Pont Neuf. To attract customers, his ‘waiters’ took coffee pots heated by small lamps around the streets shouting ‘café, café!’. Despite his enterprising strategies, Pasqua’s business never took off and he left for England where coffee was more popular at that time.

Le Procope

The first successful café was opened in 1686, by a Sicilian chef named Francois Procope. His early experiences as a ‘limonadier’ (lemonade seller) led his large and distinguished clientele to Le Procope. Located near the Comedie Francaise, Le Procope also attracted theatregoers, actors and musicians.

Its décor and furnishing were based on the aristocratic salons with gilded mirrors, ornately decorated walls and columns, marble tables and comfy seating. Parisians went there to meet and play games as well as to socialise and drink coffee.

The original Procope closed in 1872. However, a second place bearing the same name and taking its history was built in the 1920s. The current décor dates from a refurbishment in the 1980s.

Revolutionary thinkers including Robespierre, Danton and Marat also frequented Le Procope in the years leading up to the French Revolution in 1789. Many of the debates that changed the course of French history took place in cafes including Le Procope.

One of the most avid coffee consumers of the time was the philosopher Voltaire, whose favourite cafe was Le Procope. It’s said he sat at the same table and chair every day, and while thinking and writing, consumed 40 or so cups of coffee at each visit.

Another regular customer was the young Napoleon Bonaparte, then a poor artillery officer, who went to the Procope to play chess. It’s said when he didn’t have enough to pay, he was encouraged to leave his hat to ensure he came back.

Visit Le Procope today and you’ll find portraits of the revolutionaries lining the walls, a replica of Napoleon’s hat exhibited behind glass and Voltaire’s table and chair marked with his name. For an authentic experience of these times past, you can order a casserole of calf’s head or revolutionary beef served two ways.

Café de la Regence

A contemporary of Le Procope was the original Cafe de la Regence, which opened near the Palais Royal in 1681. In the 18th century it moved temporarily to the Hotel Dodun before settling at 161 Rue St Honore where it eventually became a restaurant.

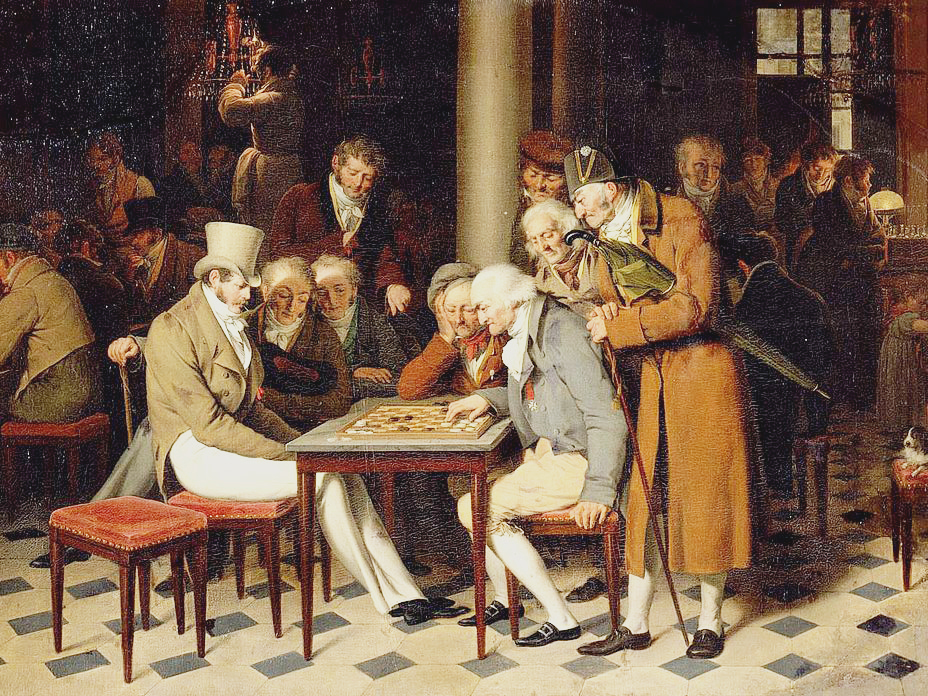

The original café was the home of chess enthusiasts from all over Europe. They smoked cigars and drank coffee while competing with each other. Tables were hired by the hour, with an extra cost for candles. Below is a painting of a chess match at the Cafe de la Regence.

It’s been said that ‘To name the patrons of the Café de la Régence in its long career would be to outline a history of French literature for more than two centuries.’ One of the most famous was Diderot. His wife gave him nine sous every day to buy coffee at the Cafe de la Regence where he wrote many philosophical and scientific works, and in 1781 co-wrote the first French Encyclopedia of seventeen folios.

Eighteenth & nineteenth century cafes

By the early eighteenth century, a bit more than a decade after Le Procope opened, there were a few hundred cafes across Paris. By the early nineteenth century there were thousands. Most of these no longer exist but their stories live on in the novels, poetry and paintings of those who were their patrons. The earliest were located in the colonnaded arcades in the grounds of the Palais Royale. Three of these were Cafe de Foy, the Royal Drummer and Café Lambin.

Café de Foy

In 1789, Camille Desmoulins incited Parisians to revolution at Café de Foy. Standing on the table, with a sword in one hand and a pistol in the other, ‘blazing with a white hot frenzy‘, he gave a long impassioned speech that led the angered crowd to storm the Bastille – the fateful event that triggered the French Revolution.

The Royal Drummer

Known for its ‘excess and low class vices’ during the reign of Louis XV, that’s not to say royalty were never seen at the Royal Drummer. Apparently Louis XV was a frequent visitor and Marie Antoinette, the wife of Louis XVI, once declared she had her most enjoyable time at a wild farandole at the Royal Drummer. A farandole is a community chain dance similar to a gavotte.

Café Lambin

Dating from 1805, Café Lambin is where those opposed to Napoleon Bonaparte met. Board games such as chess and backgammon were popular pastimes at Cafe Lambin. The painting below is of customers playing a game of checkers there.

Two nineteenth century cafes remain on opposite street corners on Boulevard Saint Germain – Les Deux Magots and Cafe de Flore. They’re both noted for the large number of literary figures who went there to socialise and write. Another of note, Café de La Paix, is the most elaborate of them all with a prime position in the Place de L’Opera.

Les Deux Magots

Everyone asks about the name! ‘Magot’ refers to an Asian figurine and you’ll find two large ones perched high on one of the columns near the entrance. It took the name of the novelty store that once occupied the original premises – and probably sold such figurines. It opened in 1812 at 23 Rue de Buci and was relocated to 6 Place Saint Germain des Prés in l873.

Cafe De Flore

Dating from 1880, Cafe de Flore takes its name from the Goddess of flowers. There’s always a colourful display of flowers and greenery cascading from the upper level balcony. Similar to Les Deux Magots, the furnishing inside is classic Art Deco with mirrors and columns, mahogany tables and red leather seats. It’s located at 172 Boulevard Saint Germain.

As a tribute to their literary clientele of the past, both cafes now offer annual prizes to authors.

Le Prix des Deux Magots came out of a discussion between a librarian and an author while drinking at Les Deux Magots in 1933. They asked 13 friends to put in 100 francs each to make up a prize of 1,300 francs for an unknown author of a less conventional novel. On hearing of the prize, the owner of Les Deux Magots offered to sponsor the award in subsequent years.

Likewise, every year since 1994, Café de Flore has offered the Prix de Flore to a young author judged by a panel of journalists. Sponsored by the café, the prize is 6,000 Euros and the opportunity of drinking a glass of Pouilly-Fume, a white wine from the Loire region, at the café every day for a year – from a glass engraved with their name

Café de la Paix

Café de la Paix opened in 1862 on the lower level of the Le Grand Hotel. Commanding an impressive view of the Opera Garnier, it attracted the patronage of actors, producers and theatregoers. Later it attracted the interest of filmmakers and has been the set for many movies – and the place where Hollywood actors and producers went in the 1950s.

One of the most elegant of the old Paris cafes, it features ceilings painted with frescoes and gilded ornamentation on panelled walls and columns. Customers can experience the classics of French gastronomy inside – or an aperitif on the terrace while watching Paris life pass by in the street.

Cafes, caffeine & creativity

Creative people of all kinds. writers, musicians, artists and philosophers frequented the early cafes of Paris seeking the stimulating effects of caffeine that opened their minds to the flow of ideas and creativity.

The famous French philosopher and writer, Honore de Balzac produced a vast number of novels and short stories; more than 90 of them being within a period of 18 years. Well aware of the power coffee had over his mind and body in ‘The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee’, he wrote ‘The coffee falls into your stomach and straight away there is commotion. Ideas begin to move like the battalions of the Grand Army on the battlefield when the battle takes place. Things remembered arrive at full gallop ensign to the wind.’

In his ‘History of France’ written in 1855, the great French historian Michelet wrote ‘Paris became one vast café. Conversation in France was at its zenith. There were less eloquence and rhetoric than in ’89. With the exception of Rousseau, there was no orator to cite. The intangible flow of wit was as spontaneous as possible. For this sparkling outburst there is no doubt that honor should be ascribed in part to the auspicious revolution of the times, to the great event which created new customs, and even modified human temperament—the advent of coffee’